Parents’ perceptions of family involvement and youth outcomes at an urban 4-H education center

December 2006, Vol. 11, No. 2

ISSN 1540 5273

Theresa M. Ferrari,

Extension Specialist, 4-H Youth Development

Ohio State University Extension

2120 Fyffe Rd., Rm. 25 Ag Admin Bldg, Columbus, OH 43210

Phone: 614.247.8164 Fax: 614.292.5937

ferrari.8@osu.edu

Ted G. Futris,

Extension Specialist, Family Life

University of Georgia

Carol A. Smathers,

CYFAR Project Coordinator

Ohio State University Extension

Graham R. Cochran,

Leader, New Personnel Development, Human Resources,

Ohio State University Extension

Nate Arnett,

Extension Educator and Director, Adventure Central

Ohio State University Extension

Janel K. Digby,

Family and Consumer Sciences Teacher

Elmwood Local Schools, Bloomdale, Ohio

Abstract

Family involvement, a characteristic of high quality youth programs, is also associated with children’s academic achievement and overall healthy development. Supported by the Children, Youth, and Families at Risk (CYFAR) New Communities Program, Adventure Central, an urban youth program in Dayton, Ohio, employed strategies to assess and address family needs and to foster sustainable family engagement. This study employed a multi-method strategy to identify parents’ (a) practices that support youths’ educational success; (b) barriers inhibiting involvement; (c) perceptions of support; (d) interests in educational programming, family involvement opportunities, and delivery method preferences; and (e) perceptions of youth outcomes. Results showed that parents currently engage in practices known to enhance educational success. Current practices at Adventure Central appear to be contributing to a safe and welcoming environment where parents feel that their child experiences a variety of educational and social benefits. The evolution of family programming at Adventure Central and implications for programs working to enhance family engagement are highlighted.

Key words: parent involvement, family engagement, urban programs, youth programs, after-school programs

Introduction

A recent review of research shows that community programs are most effective when they coordinate their activities with parents, schools, and communities (Eccles and Gootman 2002). Specifically, family involvement is a feature that has been associated with high quality programs and with children’s academic achievement and healthy development. However, there are many potential barriers to parents’ participation (Eccles and Harold 1993), and programs should work to identify and overcome these conditions. The desire to deliver a comprehensive youth and family development program motivated 4-H educators, with the support of the Children, Youth, and Families at Risk (CYFAR) program New Communities Project, to examine the level of program practices supporting educational success, parent involvement, and the outcomes resulting from youths’ participation in 4-H programming at Adventure Central, an Extension-managed urban youth education center.

Adventure Central, which has been operating since 2000, was formed as a collaboration between Ohio State University Extension’s 4-H Youth Development program, and Five Rivers MetroPark, the local park and recreation organization in Dayton, Ohio. The facility is located within a 50-acre park in the southwestern part of the city. The residents of this area are primarily African-American, with a median annual income of just over $18,000; 85 percent of youth qualify for the free and reduced-price meal program.

Adventure Central serves as a hub for out-of-school time programming such as after-school activities, a youth leadership board, workforce preparation training and work-based learning experiences, open computer labs, clubs, overnight camps, and summer day camps for school-age youth. The center is open between 2:30 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. from Monday through Thursday, and offers expanded hours in the summer. Its mission is focused on positive youth development with an emphasis on environmental education and leadership skills. Youth spend time getting help with homework, reading with volunteers, learning through hands-on activities, and forming positive relationships with caring adults. Additional information on the development of the program can be found elsewhere (Cochran, Arnett, and Ferrari 2006).

In 2003, Adventure Central was selected as one of two sites for Ohio’s New Communities Project, part of the CYFAR program (www.csrees.usda.gov/nea/family/cyfar/cyfar.html). The emphasis for the project was to enhance parent involvement in order to promote the holistic development of youth participants and to close the circle of support between home, school, and after-school settings. The implementation of this new program emphasis prompted the current study.

Review of literature

Recommendations to involve families recognize that parental involvement is key to children’s academic achievement and overall healthy development (Epstein 1991; Fan and Chen 2001; Gettinger and Guetschow 1998; Hara and Burke 1998; Jeynes 2005). Moreover, results of a recent meta-analysis indicated a “considerable and consistent relationship” between parental involvement and academic achievement specifically among urban students (Jeynes 2005, 258). These results held across race and gender.

Parental involvement is a multi-dimensional concept (Fan and Chen 2001). Furthermore, care should be taken to define parent involvement not only from the school’s perspective, but from the parents’ perspective as well (Lawson 2003). Researchers have suggested use of a broad definition of parental involvement that includes more than attendance at school events (McKay, Atkins, Hawkins, Brown, and Lynn 2003). Several specific components of parental involvement have been identified. The National Education Longitudinal Study identified four areas to consider: (a) home-school communication, (b) volunteering, (c) setting school-related rules at home, and (d) discussing school-related concerns. Epstein’s (1995) typology also includes two additional areas, parent involvement in decision making and collaboration with the community.

Within these broad areas are specific practices that are thought to promote positive development. For example, whether a parent reads with the child is an important predictor of academic outcomes for urban students (Jeynes 2005). Recent research has identified that youth monitoring, resource seeking, and in-home learning are among the strategies that parents can use to facilitate their child’s development (Jarrett 1999). Furthermore, positive parent attitudes and high expectations are important (Eccles and Harold 1993).

Programs meant to encourage parental support have a positive relationship to school achievement (Jeynes 2005). However, this research has examined parental involvement efforts connected with schools, not out-of-school programs. Recently, the Harvard Family Research Project (Caspe, Traub, and Little 2002) undertook a review of family involvement in out-of-school time programs. Their definition of family involvement in out-of-school time programs includes efforts to (a) enrich adult educational development, (b) engage with their children in meaningful shared experiences, (c) participate in program governance and community leadership, and (d) build stronger links with schools. However, little evaluation has been conducted to examine the nature and scope of family involvement and its impact on youth development in out-of-school settings. Thus, it would be important to assess parents’ current practices and perceptions in these areas in order to know how to best design programs to support their involvement in supporting their child’s development while participating in Adventure Central’s programs.

Purpose

This evaluation study sought to identify parent practices and perceptions in the following areas:

- Parents’ current involvement in practices that support youths’ educational success

- Barriers potentially inhibiting parent involvement

- Parents’ current interests in educational programming, family involvement opportunities, and their delivery method preferences

- Parents’ perceptions of the center as a supportive environment for them and their child(ren) and

- Parents’ perceptions of youth outcomes from program participation.

Methodology

This study employed a multi-method strategy that included a survey and focus groups. The university’s Institutional Review Board granted approval for the study’s procedures.

Survey

Established models of family involvement guided the overall survey development (Epstein 1995; Caspe et al. 2002; Mulroy and Bothell 2003).

Participants

A census of parents (or primary caretakers) of all youth attending Adventure Central was undertaken during January 2004 (N=64). Staff distributed the surveys at the program site (89 percent), by mail (9 percent), or directly to the home (2 percent). Up to three follow-up contacts were made to obtain the completed surveys. Fifty-four surveys were returned for an 84 percent response rate. Parents also completed one assessment for each child who attended the program (N = 95); data were received for 86 percent of the children.

The majority of the parents completing the survey were mothers (79 percent). Most were African-American females (86 percent) and were between the ages of 30 and 39 (45 percent) and 40 and 49 years old (34 percent). Most of the parents had completed at least a high school education (98 percent) and were employed full-time (79 percent). About one-third received public assistance. The family composition varied; a relatively equal percentage of children attending Adventure Central had one adult (47 percent) or two adults (49 percent) living in their current households. Most of the families had one to three children (94 percent), with a total of 95 children overall attending the program. Data were obtained for 82 youth (56 percent female). They ranged from kindergarten through 11th grade and had attended the program for varying lengths of time (ranging from 6 months to 3 years).

Measures

Items were adapted from existing measures (Bailey and Simeonsson 1991; Caldwell and Bradley 1984; Gottfried, Fleming, and Gottfried 1994). Other items were created to address areas desired by program staff.

Educational support practices. Parents responded to two sets of items reflecting parenting activities conducive to children’s academic success. First, parents were asked to report how often during the past month they engaged in nine activities (e.g., read to the child, helped with homework, or limited TV viewing) on 5-point scale: 1 (never), 2 (once or twice a month), 3 (every week), 4 (at least 3 times a week), and 5 (every day). Next, parents reported how often during the past year they participated in seven additional activities (e.g., attended child’s activity/event, volunteered, discussed future plans with child) on a 5-point scale: 1 (never), 2 (once or twice), 3 (several times), 4 (about once a month), and 5 (about once a week or more).

Barriers to participation. Nine items were derived from the parent involvement literature regarding barriers to involvement (e.g., work, child care, evening too stressful). Parents responded on a 3-point scale of 1 (never), 2 (sometimes), and 3 (often).

Parents’ interest in education and family-focused activities. Parents were asked about the degree to which they were interested in 13 topics (e.g., child growth/development, job skills) on a 3-point scale: 1 (not at all interested), 2 (somewhat interested), and 3 (interested). They also indicated their preferred delivery method and time preference by selecting from a list of five items (attending a class, receiving a newsletter, watching a video on TV, watching an interactive video on a computer, having someone visit at home), with an opportunity to add other methods.

Climate and support from Adventure Central. Eight items (adapted from Anderson-Butcher and Conroy 2002) measured on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) were used to assess the extent to which parents perceived the environment at Adventure Central to be safe and welcoming for them and their child(ren).

Perception of youth outcomes. Adapted from the New Hampshire CYFAR project, parents responded to 14 items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) reflecting how they felt their child was doing since enrolling in the center (e.g., more brave about trying new things, improved ability to communicate).

Focus groups

As a follow-up to the survey, parents were invited to participate in focus groups. Recommended procedures were used to plan the process and to construct the interview questions (Krueger 1998a; 1998b; Krueger and Casey 2000; Morgan 1997; Morgan and Scannell 1998). Questions were designed to elicit parents’ thoughts regarding their own and their child’s experience at Adventure Central and their suggestions regarding future family programming. A session was held to pilot the questions and to provide training for the focus group moderators. The moderator team consisted of two staff members from the University (the state program coordinator and a graduate research associate) and a parent from Adventure Central.

Three focus groups were conducted, with a total of 20 parents participating. Parents were offered a $20 grocery gift card as a participation incentive. Program staff members were not present during the focus group meetings. Focus group interviews were recorded and transcribed. Data were analyzed using open coding, a process of breaking down, examining, comparing, and categorizing the data (Strauss and Corbin 1990). Categories were then grouped into overarching themes. The categorization was developed by consultation between the CYFAR program coordinator (who was one of the focus group moderators) and the two project evaluators.

Results

This section reports results for the survey and focus groups. The rich description that parents provided in the focus groups gave further insight into their perceptions beyond what was evident in the survey.

Parents’ engagement in educational support activities

Parents considered their child’s educational needs when enrolling them in Adventure Central’s program. The primary reason parents gave for enrolling in the program was the opportunity for the child to learn new things (91 percent) and to obtain homework assistance (75 percent). In open-ended questions, they added that they liked the social skills that their children gain through their participation (e.g., “I like the program because it taught my child as far as his reading abilities to read and to communicate with other kids, you know, to play and things like that.”)

We found that parents were engaging to some extent in practices known to enhance educational success. For example, many of the parents indicated that during the past month they checked on whether their children completed their homework every day. On the other hand, some practices had a low frequency (e.g., very few parents were reading to their children every day). Table 1 reports the frequencies for all practices within the past month.

Table 1. Frequency of parents’ engagement in educational support activities in the past month (n = 54)

| During the past month, how often have you… |

Never % |

Once or twice a month % |

About once a week % |

At least 3 times a week % |

Every day % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Checked on whether child did homework |

0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 91 |

| Encouraged child to do well in school |

0 | 0 | 9 | 7 | 83 |

| Had a good conversation with child |

0 | 0 | 4 | 17 | 80 |

| Praised or rewarded child | 0 | 6 | 9 | 19 | 66 |

| Limited amount of time child could go out with friends on school nights |

19 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 64 |

| Offered to help child with homework |

0 | 13 | 6 | 22 | 59 |

| Limited the amount of time child could spend watching TV |

8 | 4 | 11 | 28 | 49 |

| Helped child with homework | 0 | 13 | 9 | 28 | 49 |

| Read to child | 11 | 28 | 34 | 23 | 4 |

A second set of questions asked parents to report the frequency of certain practices, this time using the past year as the frame of reference. According to our findings, parents varied in how often they engaged in these educational support activities (see Table 2). For example, about one-third of the parents frequently attended their child’s school and extracurricular activities and talked about the future. On the other hand, one quarter (26 percent) indicated that they never volunteer for another organization, and 21 percent did not volunteer at their child’s school

Table 2. Frequency of parents’ engagement in educational support activities during the past year (n=54)

| During the past year, how often have you… |

Never % |

Once or twice % |

Several times % |

Once a month % |

Once a week or more % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attended an event or activity in which child participated |

0 | 11 | 38 | 17 | 34 |

| Talked to child about plans for the future |

0 | 9 | 37 | 24 | 30 |

| Volunteered to help at child’s school |

21 | 32 | 23 | 9 | 15 |

| Taken child to library | 4 | 16 | 45 | 24 | 12 |

| Volunteered to help with another organization |

26 | 28 | 19 | 17 | 11 |

| Taken child to any type of musical or theatrical performance |

15 | 38 | 30 | 11 | 6 |

| Taken children to any type of museum |

19 | 35 | 37 | 6 | 4 |

Barriers to parent involvement

As noted in Table 3, the primary barriers to parent involvement appeared to be their work hours. Other barriers to parental involvement were their lack of time and their stressful evenings. Focus groups confirmed that work demands, scheduling conflicts, full schedules, and the lack of time and energy at the end of the day were the primary barriers to participation in parent or family programs. Conversely, almost all (96 percent) indicated that not feeling welcome by the staff was “never” a barrier. Parent comments from the focus groups supported this finding. To quote a parent:

Well, personally [the staff] all have been like co-parents for me. And they have been very helpful. If I say, “Hey, my kid didn’t do good this week,” they reinforce that. Or they’ll say, “Come here. We’re talking about responsibility.” So they have been a good resource for extended co-parents for people who don’t have two [parents] in the home.

Table 3. Barriers to parent involvement at Adventure Central (n = 47)

| Barrier | Never % |

Sometimes % |

Often % |

|---|---|---|---|

| My work hours | 21 | 40 | 38 |

| Evenings are too stressful | 39 | 54 | 7 |

| No information about activities | 57 | 36 | 6 |

| Not enough time | 38 | 58 | 4 |

| My health | 81 | 15 | 4 |

| No transportation | 83 | 15 | 2 |

| No child care | 91 | 7 | 2 |

| Feeling that my ideas don’t matter | 89 | 9 | 2 |

| Don’t feel welcomed by teachers/staff | 96 | 2 | 2 |

Parents’ interest in education and family-focused activities

We found that many parents were very interested in information that helps them locate activities for their children (94 percent) and in learning how to help their children do well in school (90 percent). Parents also indicated a high degree of interest in a variety of topics related to children’s growth and development (87 percent) and managing their child’s behavior (76 percent). Interestingly, parents were less interested in receiving help related to employment and money management. The delivery methods preferred by more than two-thirds of the parents were newsletters or evening meetings at Adventure Central. They were not as interested in having someone visit them in their homes, or in less interactive methods such as television or computer.

A majority of parents were interested in participating in family-focused activities. Forty percent stated that it was very likely that they would participate, while an additional 30 percent stated that it was fairly likely that they would participate. A primary theme of the focus group responses indicated that many parents would like programs for families to be offered on a quarterly basis. When asked what would be most important to add in the area of support for families, parents in focus groups expressed interest in the addition of professional counselors to the center staff, parent-staff conference opportunities, and program services offered after school on Fridays.

Climate and support at Adventure Central

Overall, feelings about Adventure Central were positive. Results indicated that parents strongly agreed that Adventure Central is safe place for their children, and the staff are caring and encourage their children. Furthermore, they strongly agreed that the staff members at Adventure Central are welcoming (e.g., “The kids get a lot of nurturing, love, and support. And as parents, when you walk in, you feel good.”). Parents were overwhelmingly positive about the staff, and spoke favorably about the homework assistance and program activities offered. They also supported the positive youth development philosophy. As one parent said,

4-H – the mission, and the value statements which are displayed throughout the building – are key for me. Because that’s something tangible and visible that you can see and attach to and those values are the rule of what my wife and I are trying to instill in our daughters, so that’s really been something that we’ve appreciated.

Parents’ perceptions of youth outcomes

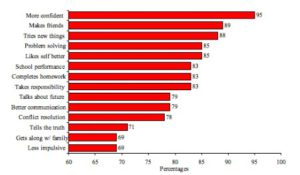

The vast majority of parents indicated that their child is experiencing a variety of educational and social benefits due to their participation in the program (see Figure 1). More than two-thirds agreed or strongly agreed that their child improved since coming to Adventure Central. Improvements in social skills and school performance were mentioned most often.

Figure 1: Parents’ perceptions of child outcomes since attending Adventure Central

[D]

Note: Combines “agree” and “strongly agree” responses

In focus groups, parents expanded on some of the benefits they perceived for their children. Again, social skills and interaction were mentioned by many parents. One parent noted that safety is an issue. “[We live in] an older neighborhood, so I’m scared to let him go and play by himself. So he gets to interact here with other kids.” Social benefits were further explained by another parent:

His social skills are so much better. Now he’s interacting with other kids, and learning [when] to go along with other kids and when to step back. And even with his schooling, it helps so much. With what he learns here, he’s taken back to school, and his teacher’s like, you know, well, what’s going on? … And she was like, ‘he’s doing so much better in school now than from when he first started the beginning of the year.’

Parents associated their children’s improved reading levels and grades with participation in Adventure Central’s program. They cited the emphasis on prioritizing homework, support offered through the reading program, and recognition of students’ achievements as factors that help develop and improve academic abilities. The time and effort devoted to encouraging the youth to complete their homework at Adventure Central is very helpful to parents, as it frees up their time and attention for other things. This was voiced by one of the parents as follows:

Well, I’m going to tell you something I’m really pleased with. … it’s been very, very helpful and very, very important and a big factor in my home, and that’s homework. You know, with a busy schedule …with juggling jobs; that was a big factor in our home, trying to get homework done. … This has been a blessing that this type of place has been established.

In addition, parents expressed that the discipline process at Adventure Central helps shape these skills and behaviors, and this supports the parents’ own family discipline efforts. In particular, they noted that discipline is “fair,” and mentioned the “steadiness and consistency” that the program brings.

Further, parents noted the development of skills not included on the survey, such as time management and working with adults.

My oldest is a part of the youth board. And I think that teaches time management because she says, ‘I have so much to do before the next meeting.’ … And I say that’s where prioritizing comes into play. You have to see what responsibility is needed and kind of go into time management skills, as well as social skills, and just dealing with other students, but also adults as well.

Finally, parents noted the opportunities that participation in Adventure Central’s programs has provided for their child.

It’s helped my son tremendously … he’s involved with a lot now. He sits on the Board and he goes on most of those overnighters, and he’s gonna be a teen assistant this year. It’s really enhanced his ability to be able to communicate. He has been to conferences; he’s been up to Columbus.

Discussion

Whereas most research on parent involvement examines it from the school perspective, this study sought to examine the experience of an out-of-school time program. It is important to explore this topic, as many after-school programs lack a family involvement component (James and Partee 2003). Yet, it is a recommended practice because research has shown the benefits of family engagement in children’s learning.

This study provided Adventure Central’s staff with specific information regarding parent practices and with the current status of their family engagement efforts. Parents appear to be engaging in a variety of practices that support their child’s educational outcomes. This is important because participation in learning-at-home activities has been related to academic achievement (Sheldon and Epstein 2005). Likewise, knowing which practices are less frequent will assist with future program planning.

Parents expressed work responsibilities as the primary barrier limiting their involvement. This barrier is similar to a survey conducted in another urban neighborhood (Cash et al. 2004). However, there were some differences in the barriers expressed, pointing out the need to understand the barriers specific to each group, rather than making assumptions. In contrast to what previous authors have noted (Eccles and Harold 1993), Adventure Central parents did not indicate that feeling unwelcome was a barrier to their participation; in fact, they expressed many positive feelings about the staff and the climate at Adventure Central. Because family involvement is more likely when families are welcomed and when trusting relationships and respect exist (Caspe et al. 2002; Christensen, Rounds, and Franklin 1992), future program efforts at Adventure Central can build on this foundation.

Parents’ desire for information on a variety of topics and for additional involvement in the program is encouraging, as such involvement is associated with greater academic achievement and other positive outcomes. Previous research had documented that youth participants viewed their relationships with adults at Adventure Central as supportive, and they identified specific staff behaviors that contributed to this perception (Paisley and Ferrari 2005). The current research extends this finding to parents as well, as they described Adventure Central as a safe and welcoming environment for both them and their children. This finding is in line with theoretical models (Eccles and Harold 1993) and research that shows that parental reports of school involvement were positively associated with school climate (McKay et al. 2003). Furthermore, parents’ comments confirmed that key features of positive youth development (e.g., Eccles and Gootman 2002; National 4-H Impact Assessment 2001) are in place in Adventure Central’s program.

Obtaining parents’ perceptions of youth outcomes provided an important perspective. An increased need for accountability makes it imperative to document youth outcomes. Clearly, parents attribute many positive outcomes to their child’s participation in Adventure Central’s program. Little evaluation has been conducted on the nature and scope of family involvement and its impacts on youth development in out-of-school time programs (Caspe et al. 2002; James and Partee 2003). Thus, this study contributes to this growing body of knowledge. Our results also support an expanded definition of parent involvement. As demonstrated here, and suggested by others (e.g., James and Partee 2003; McKay et al. 2003), parent involvement should be conceptualized to include the many ways that parents can be involved beyond being physically present at programs.

Implications

This study has several implications for those interested in encouraging parental involvement. These suggestions are also in accordance with those in recent publications focusing on engaging families in out-of-school time programs (Harris and Wimer 2004; James and Partee 2003; Kakli et al. 2006).

- Gather parents’ input to ensure that programming is on target with stated goals. Even though participation at Adventure Central is voluntary, we determined that it was important to obtain parents’ perceptions. This is one way to demonstrate support of parents.

- Identify and address barriers to parent involvement. It is important to understand the nature of barriers to parent involvement in order to identify possible solutions (Moore and Lasky 2001).

- Dedicate staff resources to parent involvement. Adventure Central employs a full-time staff member to address family involvement and connections between home, school, and after-school environments. The staff member is on-site daily at the program and makes regular contacts with parents, teachers, school officials, and community agencies. However, family engagement is also viewed as a role for all staff members. Program directors work to instill this expectation.

- Plan specific activities to engage parents and evaluate these efforts. Based on findings from this survey, the site staff developed and expanded activities to foster family involvement. These activities included Family Reading/Literacy Nights, Family Fun Nights, educational events, field trips, and camping trips with team-building activities. Evaluation of these activities showed that 100 percent of participants strongly agreed with the statement “This program was a positive experience for my family to spend time together.”

- Focus on communication to build relationships and trust. In contrast, we have found that an equally important aspect of engaging families is the informal interactions and conversations that occur. While informal, these interactions are intentional, and much parent education is embedded in these contacts.

We also offer several recommendations regarding program evaluation.

- Remember that parents represent an important source of information about their child’s outcomes. Parents are valuable sources of information regarding their child’s skill development. They may be particularly helpful regarding outcomes for young children whose communication skills, attention span, memory, self-perceptions, and ability to determine cause and effect may limit their ability to provide useful information. We found a combination of qualitative and quantitative data to be useful.

- Conduct on-going evaluation. This study is part of an on-going effort to assess program outcomes at Adventure Central, including observations, surveys, and interviews with youth, and focus groups with staff (see also Ferrari and Turner 2006; Paisley and Ferrari 2005). Furthermore, the state CYFAR staff (project directors, evaluators, and state coordinator) worked with Adventure Central’s site staff to revise the program survey instruments and implement an annual evaluation process, which will track progress and inform future program directions and enhancements.

- Use the results of surveys to inform subsequent program delivery and to align programming with recommended practices. In our case, two major strategies have been developed: (a) connecting home, school, and after-school environments through a family involvement specialist and (b) expanded offering of shared out-of-school time experiences (i.e., family involvement activities). These are two of the dimensions of working with families identified by the Harvard Family Research Project (Caspe et al. 2002).

- Communicate the results of program evaluation efforts to stakeholders. The program evaluation has been shared with key stakeholders, including parents. These results can be used to secure additional funding, an important step toward ensuring program sustainability.

Out-of-school time programs should continue to explore ways to enhance parent involvement. Continuing attention to children’s holistic development and to making connections among the settings of home, school, and after-school will strengthen these programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and parents at Adventure Central for their participation in this study.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the National Association of Extension 4-H Agents annual conference in Seattle, Washington, in November 2005.

References

Anderson-Butcher, Dawn, and David Conroy. 2002. Factorial and criterion validity of scores of a measure of belonging in youth development programs. Educational and Psychological Measurement 62(5): 857-876.

Bailey, Donald B., and Rune J. Simeonsson. 2001. Family needs survey. In Handbook of family measurement techniques, ed. B. F. Perlmutter, J. Touliatos, and G. W. Holden, 220, 389-391. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Caldwell, Bettye, and Robert H. Bradley. 1984. Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Little Rock, Arkansas: University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Center for Child Development and Education.

Cash, Scottye, David Kondrat, Dawn Anderson-Butcher, Ted G. Futris, and Theresa M. Ferrari. 2004. Implementing a process to understand parent needs in an urban neighborhood. Poster presentation at the Children, Youth, and Families at Risk (CYFAR) conference, Seattle, Washington.

Caspe, Margaret, Flora Traub, and Priscilla Little. 2002. Beyond the head count: Evaluating family involvement in out-of-school time. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Family Research Project,http://www.gse.harvard.edu/hfrp/content/projects/afterschool/resources/issuebrief4.pdf.

Christensen, Sandra L., Theresa Rounds, and Mary Jo Franklin. 1992 . Home-school collaboration: Effects, issues, and opportunities. In Home-school collaboration: Enhancing children’s academic and social competence, ed. Sandra L. Christensen and Jane C. Conoley, 19-51. Silver Spring, Maryland: National Association of School Psychologists.

Cochran, Graham, Nate Arnett, and Theresa M. Ferrari. 2006. Adventure Central: Applying the “demonstration plot” concept to youth development. Ohio State University Extension, 4-H Youth Development, Ohio State University, Columbus.

Eccles, Jacquelynne, and Jennifer A. Gootman, eds. 2002. Community programs to promote youth development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Eccles, Jacquelynne S., and Rena D. Harold. 1993. Parent-school involvement during the early adolescent years. Teacher’s College Record 94(3): 568-288.

Epstein, Joyce L. 1991. Effects on student achievement of teacher practices of parent involvement. In Advances in reading/language research, Vol. 5, Literacy through family, community, and school interaction, ed. S. Silverman. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press.

Epstein, Joyce L. 1995. School/family/community partnerships. Phi Delta Kappan 76(9): 701-712.

Fan, Xitao, and Michael Chen. 2001. Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review 13(1): 1-22.

Ferrari, Theressa M., and Cassie L. Turner. 2006. Motivations for joining and continued participation in a 4-H Afterschool program. Journal of Extension 44(4): Article No. 4RIB3, http://www.joe.org/joe/2006august/index.shtml.

Gettinger, Maribeth, and Kristen Waters Guetschow. 1998. Parental involvement in schools: Parent and teacher perceptions of roles, efficacy, and opportunities. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 32(1): 38-52.

Gottfried, Adele Eskeles, James S. Fleming, and Allen W. Gottfried. 1994. Role of parental motivational practices in children’s intrinsic motivation and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology 86: 104-113.

Hara, Steven R., and Daniel J. Burke. 1998. Parent involvement: The key to improved student achievement. School Community Journal 8(2): 9-19.

Harris, Erin, and Chris Wimer. 2004. Engaging with families in out-of-school time learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Family Research Project,http://www.gse.harvard.edu/hrfp/content/projects/afterschool/resources/snapshot4.pdf.

James, Donna W., and Glenda Partee. 2003. No more islands: Family involvement in 27 school and youth programs. Washington, D.C.: American Youth Policy Forum, http://www.aypf.org/publications/nomoreisle.

Jarrett, Robyn. 1999. Successful parenting in high risk neighborhoods. Future of Children9(2): 45-50.

Jeynes, William H. 2005. A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education 40(3): 237-269.

Kakli, Zenub, Holly Kreider, Priscilla Little, Tania Buck, and Maryellen Coffey. 2006. Focus on families! How to build and support family-centered practices in after school. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Family Research Project,http://www.gse.harvard.edu/hfrp/content/projects/afterschool/resources/families/guide.pdf.

Krueger, Richard A. 1998a. Developing questions for focus groups. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Krueger, Richard A. 1998b. Moderating focus groups. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Krueger, Richard A., and Mary A. Casey. 2000. Focus groups: A practical guise for applied research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Lawson, Michael A. 2003. School-family relations in context: Parent and teacher perceptions of parent involvement. Urban Education 38(1): 77-133.

McKay, Mary McKernan, Mark S. Atkins, Tracie Hawkins, Catherine Brown, and Cynthia J. Lynn. 2003. Inner-city African American parental involvement in children’s schooling: Racial socialization and social support from the parent community. American Journal of Community Psychology 32(1/2): 107-114.

Moore, Shawn, and Sue Lasky. 2001. Parental involvement in education. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, International Centre for Educational Change.

Morgan, David L. 1997. Focus groups as qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Morgan, David L., and Alice U. Scannell. 1998. Planning focus groups. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Mulroy, Maureen T., and Joan Bothell. 2003. Supporting family involvement in children’s learning. Storrs: University of Connecticut.

National 4-H Impact Assessment. 2001. Prepared and engaged youth. Washington, D.C.: CSREES/USDA, National 4-H Headquarters, http://www.national4-hheadquarters.gov/impact.htm.

Paisley, Jessica E., and Theresa M. Ferrari. 2005. Extent of positive youth-adults relationship in a 4-H Afterschool program. Journal of Extension 43(2): Article No. 2RIB4, http://www.joe.org/joe/2005april/rb4.shtml.

Sheldon, Steven B., and Joyce L. Epstein. (2005). Involvement counts: Family and community partnerships and mathematics achievement. Journal of Educational Research 98(4): 196-206.

Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1990. Basics of qualitative research. Newbury Park, California: Sage.

Back to table of contents ->https://www.theforumjournal.org/2017/09/03/december-2006-vol-11-no-2/