Farmers Markets: Barriers and Pathways for Limited-Resource Consumers

Farmers Markets: Barriers and Pathways for Limited-Resource Consumers

Christopher Sneed

The University of Tennessee

Abstract

While the growth of farmers markets is heralded as exciting news among local food enthusiasts, the unfortunate reality is that the increase in the number of farmers markets has disproportionately served communities and individuals of higher socio-economic status (Jones and Bhatia 2011). This paper seeks to shed light on the inequalities surrounding farmers markets. However, more than simply pointing out these inequalities, this paper seeks to outline strategies by which farmers markets can move toward a more inclusive customer base. This paper begins with an overview chronicling the rise of farmers markets in the United States. Federally funded programs designed to increase access to farmers markets by limited-resource families are described. Following this, barriers inhibiting limited-resource individuals from engaging with farmers markets are considered. Programs that have been implemented to foster increased use of farmers markets by limited-resource families are presented. The paper concludes with recommendations for future research.

Keywords

farmers market, limited-resource, consumers

Introduction

From parking lots to community parks, the number of farmers markets dotting the food landscape has increased exponentially (USDA 2015a). This increase has been welcomed as an opportunity benefiting both farmers and consumers. With this increase come hopes for a more sustainable food system (Alkon and McCullen 2011), increased community connections (Hinrichs 2000), reduced rates of obesity trends (CDC 2009), and improvements in the economic and physical well-being of residents served by the markets (Jones and Bhatia 2011).

The potential benefits of farmers markets along with their increased popularity among consumers masks an underlying and unsettling reality. Farmers markets (as well as other alternative food systems) disproportionately serve communities and residents of higher socio-economic status (Alkon and McCullen 2011). The siting of markets in affluent communities, the focus of certain markets on exclusive food offerings, and the limited ability for individuals receiving federal food assistance to use their benefits at markets serve as barriers preventing limited-resource consumers from fully engaging in farmers markets. Thus, limited-resource consumers are left with limited hope for realizing the numerous benefits which have been ascribed to farmers markets.

Purpose

This paper seeks to shed light on the inequalities surrounding farmers markets. However, more than simply pointing out these inequalities, this paper seeks to outline strategies by which farmers markets can move toward a more inclusive customer base especially a customer base that includes consumers of lower socio-economic status. This paper begins with an overview chronicling the rise of farmers markets in the United States. Potential benefits of this growth are discussed. Federally funded programs designed to increase access to farmers markets by limited-resource families are described with particular attention given to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) redemption at the markets. Following this, barriers inhibiting limited-resource individuals from engaging with farmers markets are considered. Programs that have been implemented to foster increased use of farmers markets by limited-resource families are presented. The paper concludes with recommendations for future research.

Literature review

Rise of farmers markets

Farmers markets represent one of the fastest growing forms of direct farm marketing in the nation. The number of farmers markets dotting the landscape has increased significantly from 1,755 markets in 1994 to 8,492 markets in 2015 (USDA 2015a). Farmers markets both large and small exist in every state operating in both rural and urban areas (Hinrichs 2000). This growth of farmers markets has afforded consumers with increased access to a variety of high quality foods particularly locally grown produce items. Additionally, the growth of farmers markets has been touted for its positive contributions to the health of community members, effective revitalization of communities, and potential for combating the obesity epidemic (Young, Karpyn, Uy, Wich and Glyn 2011).

While the growth of farmers markets is heralded as exciting news among local food enthusiasts, the unfortunate reality is that the increase in the number of farmers markets has disproportionately served and benefited communities and individuals of higher socio-economic status (Jones and Bhatia 2011). According to Freedman, Bell, and Collins (2011), the benefits of farmers market growth are limited to the consumers served by these markets, namely white, middle-age, middle- to upper-class, well-educated individuals. The fact that many farmers markets are not located in minority and lower-income communities often means the members of these communities cannot shop (due to transportation barriers) or do not shop (due to preconceived notions about the markets) farmers markets and therefore fail to realize benefits afforded by the farmers markets. In their ethnographic study of California farmers markets, Alkon and McCullen (2011, p. 937) contend the “affluent, liberal habitus of whiteness” of farmers markets masks the inequalities inherent in this growing form of direct farm marketing. This habitus of whiteness is evident in the cultural norms that help inform the structure and function of some farmers markets. These cultural norms influence all aspects of those markets including the vendors selling at the markets, the products being offered, and the types of promotional and market events planned (Alkon and McCullen 2011).

Federal food programs and farmers markets

Currently, three federally sponsored food assistance programs (WIC Farmers Market Nutrition Program, Senior Farmers Market Nutrition Program, and SNAP) work to facilitate access of low-income families to foods available through farmers markets (USDA 2015b). Of the programs, WIC Farmers Market Nutrition Program and the Senior Farmers Market Nutrition Program have both proven to be highly effective in facilitating qualifying families’ access to farmers markets and the food products sold at these markets (Young et al. 2011).

Unfortunately, the use of SNAP (formerly Food Stamps) as a conduit for increasing farmers market participation among limited-resource families remains underutilized with two-thirds of farmers markets nationwide lacking the necessary equipment or authorization to process SNAP/ EBT benefits (Rejto 2015). The fact that SNAP benefits are yet to be accepted by all farmers markets and the low rate of redemption at farmers markets which do accept them is troubling especially given that overall SNAP has the highest participation rate of all three federally sponsored food assistance programs (Young et al. 2011).

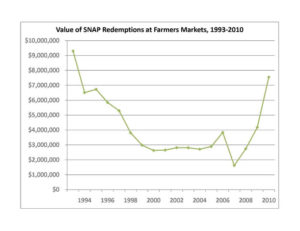

Figure 1: Value of SNAP redemption 1993 to 2010

[Figure 1 Summary: This figure shows the value of SNAP redemption at farmers markets from 1993 to 2010. SNAP redemption in 1993 was more than $9 million. SNAP redemption fell around 1999 to a low of less than $3 million. SNAP redemption began to increase, reaching more than $7 million, in 2010.]

The graph in Figure 1 depicts the value of SNAP redemption at farmers markets from 1993 to 2010 (USDA 2010). As evidenced by the graph, SNAP redemption at farmers markets remained consistently low between the years of 1996 and 2004. During this period, the traditional voucher system which characterized SNAP (food stamps) for years was converted to today’s electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system. While this transition from paper to electronic redemption has been seen as beneficial by almost all associated with SNAP, the transition did create a digital divide between traditional food retailers and farmers markets (USDA 2010). Traditional brick and mortar retailers were able to adopt and implement technologies necessary for accepting the new EBT cards. The traditional nature of their store environments meant network connections, telephone lines, and electrical power were readily accessible or could easily be installed. Unfortunately, such infrastructure was not available at farmers markets, especially those markets that operated in public spaces, parking areas, and other temporary locations. Wireless technology that would have enabled these farmers markets to accept EBT benefits was simply unobtainable or too costly for use.

The decline in SNAP/EBT redemption at farmers markets has begun to resolve as new technologies and growing encouragement by the federal government is making SNAP redemption at farmers markets more commonplace (USDA 2015b). This is welcomed news since increasing SNAP redemption at farmers markets is vitally important in creating equitable access to these markets by limited-resource families (Jones and Bhatia, 2011).

Barriers to farmers market participation

Limited-resource consumers wishing to shop farmers markets are often faced by a barrage of barriers. One of the chief barriers confronting these consumers is the sheer paucity of farmers markets operating in lower income communities (Jones and Bhatia 2011). Most farmers markets draw their customer base from surrounding neighborhoods where they are located (Brown 2002). Thus, the lack of farmers markets in limited-resource communities often means individuals living in these communities are cut off from the high quality foods sold at farmers markets. This lack of access to farmers markets combined with issues of food security across limited-resource areas works to create a perfect storm whereby limited-resource consumers are unable or severely challenged to find food resources of high quality and high nutritional value (Duram 2010).

Additionally, the brand identity of some farmers markets serves as a barrier inhibiting limited-resource consumers from shopping the markets. Brand identity encompasses the value and appeal a company communicates to its consumers (Ghodeswar 2008). In the context of farmers markets, an exclusive brand identity can be created and communicated to consumers through marketing messages, the types of products offered, as well as the types of vendors selling at the market.

Many direct agricultural markets – including farmers markets – have as their focus an exclusive consumer base (Hinrichs 2000). Through product offerings, promotional activities, and messaging, these farmers markets appeal to this base with exclusive products that are often beyond the price point of limited-resource families. Such messages of exclusivity fail to resonate with limited-resource consumers who, due to economic constraints, are price sensitive (Young et al. 2011).

Finally, for many limited-resource consumers, a lack of awareness prevents them from patronizing farmers markets. In their study of low-income North Carolinians, the top barriers preventing limited-resource individuals from shopping farmers markets included the inability of these consumers to use their EBT cards or WIC vouchers at the markets, a lack of awareness concerning the location of farmers markets in their communities, and lack of knowledge concerning farmers market hours (Leone et al. 2012). These findings are echoed by Wetherill and Gray (2015) who in their study of SNAP consumers found accessibility, awareness, and cultural barriers hindered SNAP consumers from using farmers markets.

Strategies to increase participation among limited-resource individuals

Recognizing the numerous barriers facing limited-resource consumers wishing to shop farmers markets, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has begun to focus on strategies designed to facilitate low-income consumers’ access to farmers markets and the healthy foods sold at these markets. Strategies including a focus on locating farmers markets in low-income communities, monetary incentives through dollar-matching programs, and educational outreach have become priorities of USDA within recent years.

Farmers markets have emerged as an important strategy to address the rising problem of food insecurity in limited-resource areas (Giang, Karpyn, Laurison, Hillier, and Perry 2008). Yet, few farmers markets are actually located in limited-resource neighborhoods (Jones and Bhatia 2011). To address the lack of farmers markets in these communities, non-profit organizations have begun working to establish and sustain farmers markets in under-served areas. The success of such markets, however, is often tenuous as markets in limited-resource areas must address challenges such as price constraints, food insecurity, and pronounced community needs (Young et al. 2011). Despite these challenges, farmers markets located in limited-resource communities have experienced success with some markets not only surviving, but thriving, in limited-resource communities (Young et al. 2011).

One means of drawing limited-resource consumers to farmers markets is the use of incentive programs. These incentive programs can take many forms, including the matching or doubling of SNAP benefits to be used at the markets up to a selected dollar value. According to Community Science (2013), approximately half of all farmers markets accepting SNAP benefits report to be engaging in some form of incentive program targeting limited-resource consumers. Many of these programs – especially those offering monetary incentives – are funded through partnerships between farmers markets and non-profit organizations. One such organization which has been a leader in monetary incentive programs is Michigan-based Fair Food Network. Through the work of Fair Food Network, more than 150 farmers markets in Michigan are now offering the Double Up Bucks program whereby SNAP benefits are matched dollar-for-dollar. Results from their 2014 survey of 559 consumers participating in the Double Up program show positive benefits for the participants. Of those consumers responding, 87 percent reported increased fruit and vegetable consumption as a result of participating in the Double Up program. Additionally, 67 percent reported trying new, healthier foods as a result of the program. As of 2014, Michigan ranked third in the nation for SNAP redemption at farmers markets increasing SNAP redemption at these markets from less than $16,000 in 2007 to $1.6 million in 2014 (Fair Food Network 2015).

Such positive outcomes, however, are not limited to Michigan. Other similar incentive programs have proven of benefit to limited-resource consumers across the United States. In 2012, a national cluster evaluation was conducted of farmers market incentive programs. This evaluation found nearly 75 percent of consumers participating in a farmers market incentive program reported increased fruit and vegetable consumption as a result of the incentive program (Community Science 2013). Numerous consumers reported the increased purchasing power afforded by the incentive programs gave them the opportunity to purchase fruits and vegetables, items they believed to be outside of their food budgets.

In addition to incentive programs, educational interventions including food demonstrations, cooking classes, and social marketing efforts have been implemented at farmers markets. The goal of such interventions is to increase limited-resource individuals’ familiarity with ways to select, prepare, and store the produce items available at farmers markets. One such program, the Veggie Project, was implemented to increase access and consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables in four low-income, minority communities in middle Tennessee. Through the use of educational activities and a loyalty shopper program, this program was successful in increasing access to and consumption of healthy foods among the target population (Freedman, Bell, and Collins 2011). Participation in similar farmers market educational efforts have been found to be effective for limited-resource consumers, reducing their knowledge barriers and increasing their food preparation skills. (Durward, LeBlanc, Wengreen, and Savoie 2015).

Recommendations for future research

As attention is focused on farmers markets and disparities faced by limited-resource consumers, there exist ample opportunities for additional research activities. Particularly, this research should be focused on helping to better understand pathways by which access to farmers markets by limited-resource consumers can be facilitated. Such research could seek to address questions such as the following:

- What are limited-resource consumers’ perceptions and interests regarding farmers markets?

- What role can mobile farmers markets play in addressing issues of food access for limited-resource consumers?

- To what degree can acceptance of SNAP/EBT benefits be facilitated in small farmers markets?

- What suggestions do limited-resource consumers offer for increasing their access to farmers markets?

- How can successful incentive programs be replicated? How can these programs be sustained beyond their initial funding periods?

- To what degree are educational initiatives at farmers markets effective in promoting healthy lifestyle choices among limited resource individuals?

Conclusion

The benefits ascribed to farmers markets should not be limited to one sector of the population. Instead, diligent efforts must be made to ensure these benefits are extended to other population groups, especially those of lower socio-economic status. Tools and resources for ensuring equal access to farmers markets by limited-resource consumers are already in place and proving to be effective. What remains, however, is a continued and diligent focus among local food advocates, social service workers, government agencies, and nonprofit organization to ensuring that limited-resource consumers have access to farmers markets. With this access, limited-resource consumers can enjoy more than fresh, local foods, they can enjoy the benefits ascribed to farmers markets – improved health, improved community, and improved well-being.

References

Alkon, A. H., and C. G. McCullen. 2011. “Whiteness and farmers markets: Performances, perpetuations… contestations?” Antipode 43(4): 937-959.

Brown, A. 2002. Farmers’ market research 1940-2000: An inventory and review. American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 17(4): 167-176.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2009. State indicator report on fruits and vegetables: National action guide. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

Community Science. 2013. SNAP healthy food incentives cluster evaluation 2013 final report. Gaithersburg, MD: Community Science.

Duram, L. A. 2010. Encyclopedia of organic, sustainable, and local food. Denver, CO: Greenwood.

Durward, C., H. LeBlanc, H. Wengreen, and M. Savoie. 2015. “Farmers’ Market Incentives and Nutrition Education: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior47(4): S36.

Fair Food Network. 2015. “Double up reports from the field #1: Double up in farmers’ markets: The consumer experience.” http://www.fairfoodnetwork.org/sites/default/files/Diet%20Behavior%20Report_digital.pdf

Freedman, D. A., B. A. Bell, and L. V. Collins. 2011. “The Veggie Project: a case study of a multi-component farmers’ market intervention.” The Journal of Primary Prevention, 32(3-4): 213-224.

Ghodeswar, B. M. 2008. “Building brand identity in competitive markets: a conceptual model.” Journal of Product and Brand Management 17(1): 4-12.

Giang, T., A. Karpyn, H. B. Laurison, A. Hillier, and R. D. Perry. 2008. “Closing the grocery gap in underserved communities: The creation of the Pennsylvania fresh food financing initiative.” Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 14(3): 272-279.

Hinrichs, C. C. 2000. “Embeddedness and local food systems: notes on two types of direct agricultural market.” Journal of Rural Studies 16(3): 295-303.

Jones, P. and Bhatia, R. 2011. “Supporting equitable food systems through food assistance at farmers’ markets.” American Journal of Public Health 101(5): 781-782.

Leone, L. A., D. Beth, S. B. Ickes, K. MacGuire, E. Nelson, R. A. Smith, D. F. Tate, and A. S. Ammerma/n. 2012. “Attitudes toward fruit and vegetable consumption and farmers’ market usage among low-income North Carolinians.” Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition7(1): 64-76.

Rejto, D. B. 2015. “SNAP at farmers’ markets growing, but limited by barriers (Web log post, June 10). http://farmersmarketcoalition.org/snap-at-farmers-markets-growing-but-limited-by-barriers/

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Agriculture Marketing Service. 2015a. Local food directories: National farmers market directory.http://www.ams.usda.gov/local-food-directories/farmersmarkets

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Food and Nutrition Service. 2015b. Learn about SNAP benefits at farmers markets. http://www.fns.usda.gov/ebt/learn-about-snap-benefits-farmers-markets

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrition Service. 2010. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: Feasibility of implementing electronic benefit transfer systems in farmers’ markets. http://www.fns.usda.gov/multimedia/zsx7uuuuuuu8mmmmmmmmm,

Wetherill, M. S., and K. A. Gray. 2015. “Farmers’ markets and the local food environment: Identifying perceived accessibility barriers for SNAP consumers receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) in an urban Oklahoma community.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 47(2): 127-133.

Young, C., A. Karpyn, N. Uy, K. Wich, and J. Glyn. 2011. “Farmers’ markets in low income communities: Impact of community environment, food programs and public policy.” Community Development 42(2): 208-220.

Back to table of contents ->https://www.theforumjournal.org/2017/08/29/winter-2016-vol-20-no-3/